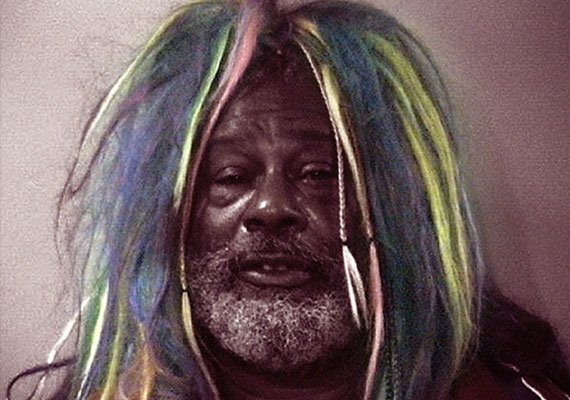

George Clinton

The Parliament Funkadelic Pioneer on Creating His Own Language, Maggot Brain, and Booty Snatching Aliens

:: for The Stranger

“If it wasn’t weird, that was weird.”

To think of funk music without George Clinton is like thinking about the breeze without air. Or water without wetness. That's how integral the man is and was to the sound. The 80-year-old Clinton is, at the core, a grand communicator and skilled facilitator—able to take 20 people in a studio noodling and jamming and pull the strings that would bring it all together. In the late 1960s, Clinton and his musical conglomerations of Parliament and Funkadelic ushered in the funk movement. Clinton aptly orchestrated and groomed the likes of Bootsy Collins, Eddie Hazel, Bernie Worrell, and Maceo Parker, stirring them all into a sonic combination that was impossible not to move to.

Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic dominated music in the 1970s with more than 40 R&B hits (which included three number ones and three platinum albums). Live, the show became an otherworldly circus. There was the Aqua Boogie Bird, the Brides of Funkenstein, the Booty Snatchers, 20-foot shades, a pyramid, a spaceship, all consumed in gyration. Despite the spectacle, what never got buried was the musicianship. Clinton spoke.

Print Version

Parliament-Funkadelic were so distinctive that you all needed your own language. There was the music, the show, and your own vocabulary. Where did that come from?

We'd be in the studio or on the road with each other, sort of shut off from the outside world—I guess it just came out of that. It wasn't like we tried to make up all these different words or ways of saying things, they just happened. On sleeve notes to the fans, one of the notes said: "Improve Your Funkmenship. The Nastified Secret Order of the United Maggots of Funkadelia is being magnetized for your convenience. Send all inquiries to Maggotropolis of Funkadelia, Los Angeles, CA. Warning: Obvious squares and turkeys attempting entry into the REALM will be reduced immediately to basic atoms of radioactive turds." Now, what that means exactly I can't say [laughs]. But you listen to the music and see the show, and you understand what it means.

You differed from James Brown's approach. He was strict, telling his players what to play, docking their pay when they were late, not allowing drugs or drinking. You were sort of the opposite.

In the studio, I say, "Do what they tell you not to do. I can always take it off." I didn't want boundaries. I wanted to take it somewhere different. I say do what you feel, always. For "Maggot Brain," Eddie Hazel came in one day and was feeling weird and down. I surrounded him with Marshall amps and told him to play like he'd just found out his mother had died. There were other instruments on the recording originally, but his guitars said so much by themselves, I pulled the other tracks. He did it in one take.

What's the weirdest thing you ever saw happen onstage?

We had people in diapers, creatures, elephant noses, a spaceship. I saw some aliens up in there. Booty snatching. If it wasn't weird, that was weird.

You've been battling record labels over the years to win back the rights to your music. You won a lawsuit in 2005 that returned ownership of Funkadelic songs to you. What's the status on that?

The status is that crooks never win. I'm kicking their ass. Yeah, I should've been looking at it all a lot closer a long time ago, but I'm going to get my shit back for my family, and for the bands' families—it's ours, not theirs. We're getting the word out and we hope to expose the practices of these companies like BMI. We launched our site entirely dedicated to the issue, to share what we've been going through. I'm raising my voice for everyone who has been cheated out of royalty checks.

Will you get it all back?

We won't get it all back, but it's a start. This year is big because it's the first year artists will be able to file for termination of these contracts.

You've been doing music for 50 years. How are you able to keep going? You've obviously been eating your veggies all these years.

When you love what you do, you don't wanna stop, and it's not a problem. I'm feeling fresh. We're eager up there. You can't stop the funk. I've cleaned some things up these past few years and I've got renewed energy. I mean, I've always had energy for playing music, but now I'm not spending that energy on finding and doing drugs—that'll suck it out of you, and I'm not wasting my money on it now. You can't be spaced-out and still do the things you need to do. Me being in a clean headspace has also helped in the fight against these companies like BMI—they thought I'd be out of commission, but I'm still here. Right here!

What do you see out there now, as far as acts?

I like Kanye, with "All the Lights." And Drake, he's pushing some buttons out there. With rappers, I see some repetitiveness—people looking the same, sounding the same. Do something different! Just 'cause you got the tattoos and the teeth don't mean you got the hooks or the music.

Looking back for a second, what have been your turning points?

When I heard the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's album, it changed my thinking—got me thinking about music and albums as a concept thing. I'd also say when Bootsy and the boys came over from James Brown. Bootsy helped me find the one. One-two-three-four-ONE. Everything is based on that one. Let's see, we played in Boston, dropped acid, wore the costumes, and went completely out of our minds. That's the way it was, we were on our own thing. On the music side, or the technical side, you could say things like finding some sounds. Like on "Flash Light," 1978, Bernie Worrell hooked up some Moogs, and we got that electronic bass sound—we took it into the '80s. Then there's Anthony Kiedis and Red Hot Chili Peppers: I produced them and we got Freaky Styley[laughs]. Then comes the hiphop—Dre, Ice Cube, De La Soul, Digital Underground, Public Enemy. It's a beautiful thing. Got the groove going with it. Funk is the DNA of hiphop, you know.